Sarah Kemble Knight's "good hard money" in 1704 was the Bay shilling, which is now called the Pine Tree shilling. Neither were found in the bay or made from trees. So why were they named such?

I'm forced to quote Shakespeare, "What is in a name? that which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet;..." Juliet is basically saying a thing is a thing regardless of its name. The same is true for Knight's money.

So why is the naming important? Because one name occurs in 1704 and the other in 2013. The naming of things is how cultures identify their objects. It establishes the human interactions with objects and its effects. Basically, names tell stories.

In 1704, the Bay shilling was termed because it was coined in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. It emphasizes the location and the time period in which it was made, the conditions of government and the personality of the colony. England was refusing to provide the colony with coins in the mid 1600s since they were strapped for coins as well. In the absence of official standard, the colonist decided to strike their own coins. That just might have been one of the first strikes of colonial independence.

Today the shilling is called the Pine Tree Shilling because, well, look at it. It has a pine tree on it. It describes the thing, emphasizing the physical characteristics of the object. The naming has lost an important cultural emphasis. Even though the two names are the same object, they are expressions of two different cultures.

Which is more "real," the one on exhibit at the Smithsonian or the one in Sarah Kemble Knight's Journal? Smithsonian coin is real in the senses. It can be seen, touched, tasted (if gotten past extensive security and you don't mind federal imprisonment). It is physical, existing in the present. However Knight's coin is immaterial existing in the past as an expression of words into an idea. Yet, it is real because it communicates the culture of the thing.

A name is more than just a name. A thing is more than just a thing.

Word Count: 359

Total Edits: 0

Wednesday, August 28, 2013

Monday, August 26, 2013

Taste Test - Sarah Kemble Knight's Journal

*Warning: Taste Tests are an attempt to explore thoughts utilizing processes similar to the creation of new recipes. We don't know what the final product will be until it's done."

1704-1705 Sarah Kemble Knight keeps the Private Journal of a Journey from Boston to New York (pub. 1825)

Pay is grain, pork, beef &c. at the prices set by the General Court that year: money is pieces of eight, rials or Boston or Bay shillings (as they call them,) or good hard money, as sometimes silver coin is termed by them;..."

"Good hard money." How I smiled when I read that, "hard money." It's real, it's an object, it's a thing. Yet, it's not. The object consists of words written on a page. It is the expression of an idea. The pages which the idea was written are the object. It is an artifact of paper, ink and glue. But the language, thoughts and voices are not material artifacts. They are immaterial artifacts called 'ideofacts.'

How do you study the things in texts, things like money or ribbons? These are objects without physical substance in our world today. I can't go to a museum and see the silver coin Madam Knight used in 1704 while at a merchant's house. Yet through her writing, the silver coin is very real to me. It has substance, it is an object, it is a thing though it is immaterial. It is another 'ideofact.'

How do I study an 'ideofact' within an 'ideofact'? How do I examine the materiality of an immaterial object within literary texts?

From a historian's perspective, this is an important question. Historians often use texts and primary sources to research and extrapolate possible answers explaining the past. I know we do this, but what's the theory and thought process behind it? What is the approach for studying material culture in literature?

My reading list begins with Doing Cultural Studies: the Story of the Sony Walkman. I'll also include the works of Raymond Williams, Roland Barthes and Bruno Latour.

Word Count: 290

Total Edits: 0

Friday, August 23, 2013

Ingredient: Stir Up the Confusion

I am often confused. For many people, confusion is uncomfortable which leads to stagnation. Somehow, "I'm confused," turns into, "I don't know," - The End.

I am often confused. For many people, confusion is uncomfortable which leads to stagnation. Somehow, "I'm confused," turns into, "I don't know," - The End. Noooooooo. "I'm confused," needs to turn into, "Why or What is it about this that is confusing?" Don't be afraid to admit your own confusion. I very timidly admitted this in my 7000 Ph.D. class about a certain reading and the professor exclaimed, "Yes! Confusion is good." When you're confused it's a pretty good indicator that there's something you need to take a closer look at.

Whatever is making you confused is probably making someone else confused too. Think about it. Which would you rather read: A) something explaining something you already know and understand, or B) something that explains something you don't know or understand. Write about what confuses you. You may not figure it out but I bet you'll end up with some good questions and great material.

Word Count: 155

Total Edits: 0

Wednesday, August 21, 2013

Riddikulus!

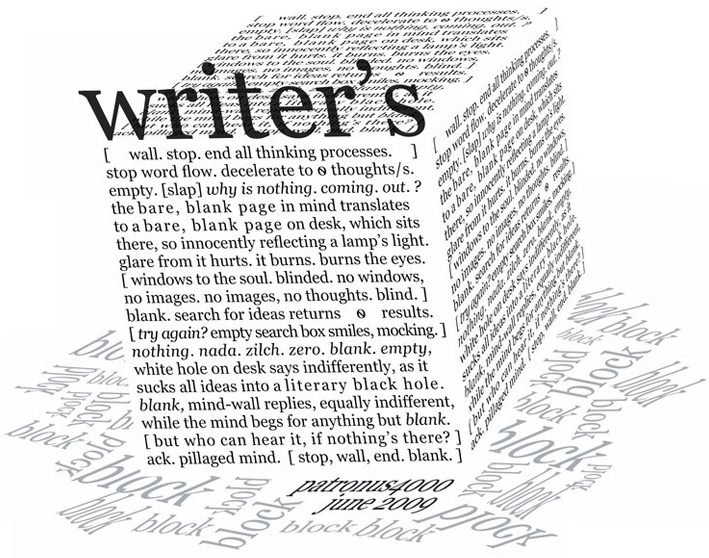

While I had writer's block I decided to play around with, what I figured was a lame, figure-of-speech exercise. During the course of playing with words I rediscovered the fun. I laughed at myself. Even better, I was able to laugh at what I was writing. I didn't take is so seriously anymore. Then I was able to write without constraints.

I think, like many other people, I get wound up in the schedule of life, "You have to write," and "You have a deadline." All this pressure builds up slowing down and even preventing the flow of writing. Therefore my recipe for encountering extreme seriousness is to do the exact opposite. Write about something lame, stupid or ridiculous. Think of writer's block as your Boggart and use the Riddikulus! charm to turn it into something fun.

Word Count: 137

Total Edits: 0

I think, like many other people, I get wound up in the schedule of life, "You have to write," and "You have a deadline." All this pressure builds up slowing down and even preventing the flow of writing. Therefore my recipe for encountering extreme seriousness is to do the exact opposite. Write about something lame, stupid or ridiculous. Think of writer's block as your Boggart and use the Riddikulus! charm to turn it into something fun.

Word Count: 137

Total Edits: 0

Monday, August 19, 2013

Writer's Block is Like...

I'm in between classes. I'm relaxing. I'm in my down time. Why can't I write? Everything I've read about this process says "just write" or "be creative." If I could write and be creative would't I'd done that already. I really didn't want to write about writer's block because who knows how many times that subject might make an appearance on the blog.

Well, I figure I'll come up with a new exercise which will use the figure of speech to find different ways to describe writer's block. It's lame, but at least it's something to write about.

Adjunction - Blocked is the writer.

Alliteration -The writer writes wetly. (Oh, that's awful. Let's try again.) The writer's block beats badly. (Blah! Let's try again.) The blocked mind mocks me. (Yeah. That's better.)

Allusion - I feel like the bard on his worst day. (Actually, it's an 'antonomasia' too.)

Anastrophe - Write I can not but try I shall.

Anaphora - I cannot write. I cannot scribe. I cannot type.

Antithesis - Writer's block is easy on the hands and hard on the mind.

Climax - Writers suffer blockage, blockage stifles creativity, creativity will burst the dams.

Hyperbole - I'll never write again.

Irony - I wrote an excellent article about writer's block.

Litotes - I am not unfamiliar with the concept of writer's block.

Metaphor - The writer's block is a black-hole of ideas.

Paradox - Blocked writers are full of ideas.

Onomatopoeia - The writer's mind whispers wind.

Oxymoron - Blocked writing.

Paralipsis - I will not dwell on the emptiness of my pages.

Personification - The blank page screamed silence.

Simile - Writer's block is like slamming into a brick wall.

Zeugma - The writer opened her mind and her pen to the page.

I think this worked. It reminded me that I need to laugh and have fun. It's harder to crack a blockade if I'm taking myself too seriously.

Word Count: 331

Total Edits: 0

Well, I figure I'll come up with a new exercise which will use the figure of speech to find different ways to describe writer's block. It's lame, but at least it's something to write about.

Adjunction - Blocked is the writer.

Alliteration -

Allusion - I feel like the bard on his worst day. (Actually, it's an 'antonomasia' too.)

Anastrophe - Write I can not but try I shall.

Anaphora - I cannot write. I cannot scribe. I cannot type.

Antithesis - Writer's block is easy on the hands and hard on the mind.

Climax - Writers suffer blockage, blockage stifles creativity, creativity will burst the dams.

Hyperbole - I'll never write again.

Irony - I wrote an excellent article about writer's block.

Litotes - I am not unfamiliar with the concept of writer's block.

Metaphor - The writer's block is a black-hole of ideas.

Paradox - Blocked writers are full of ideas.

Onomatopoeia - The writer's mind whispers wind.

Oxymoron - Blocked writing.

Paralipsis - I will not dwell on the emptiness of my pages.

Personification - The blank page screamed silence.

Simile - Writer's block is like slamming into a brick wall.

Zeugma - The writer opened her mind and her pen to the page.

I think this worked. It reminded me that I need to laugh and have fun. It's harder to crack a blockade if I'm taking myself too seriously.

Word Count: 331

Total Edits: 0

Friday, August 16, 2013

Recipe Tweak - 1st Sentence ReWrites

With great trepidation, I scattered the dust on my collection of final papers for the past 18 months of doctoral classes. After making a list of the first sentences, my face was in a perpetual pucker. Please let me apologize now to all my poor suffering professors. Regretfully, there are many sour sentences to choose from. So for the sake of my self-esteem, I chose only three to review and rewrite.

How do I take sentences like these and not send the reader into a coma after the first period? Let’s start at the beginning by comparing the content of the sentence to some that I like (see “Add Salt”) then reconstruct the words.

Sentence 1:

“The plow or plough is an agricultural tillage tool, one of the earliest designed tools continually use through history.” - A Visual Exploration of the Plow

Yawn. The sentence is archaic academia. I see a sentence like that and think, “Wow! I bored my professor before I started.”

This sentence is focused on an object much like the sentence from The Plantation Hoe and Cultural Rhetoric of Women’s Corsets. Both use personification to enhance the sentence. Let's try personifying the plow: “immortal plow.” Also, there is some alliteration with “tillage tool” which I can expand to: “agricultural tillage tool trudging through history.” Next is to include the word “art.” Put it together and I have… Ta dah! “The immortal plow is an agricultural tillage tool which has trudged through history seeding the arts.” Are you interested now? This might have been a fluke. Let’s see if I can do it again.

Sentence 2:

“Edgar Allan Poe is credited as the “Father of Detective Stories” creating a template for detective stories through three short stories: “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” “The Mystery of Marie Roget,” and “The Purloined Letter”.” – Cluing In to Edgar Allan Poe’s “Clews”

You have no clue how much fun I had reading these stories and writing this paper. Sure it was academic but it was far from boring.

Narrative and Class in a Culture of Consumption and The Ideas in Things shared some similar qualities. Using them as a template, I focused on alliteration, allusion, metaphor and idiom. I use “stories” a lot (3x in 1 sentence) so why not play with that: “stories of slashers, the Seine and sheets in plain sight.” Once I wrote that, I was able to write the remainder: “Edgar Allan Poe created three stories of slashers, the Seine and sheets in plain sight molding mystery and a new type of detective fiction on the page.” I may have to watch the alliteration use because it can be overdone.

Sentence 3:

“Museums have been and continue to be part of the landscape of major and growing towns and cities since the 1700s.” – Paris Museums and Early Modern Urban Planning

Zzzzzzzzzzzzz. Oh! There’s more?

For this sentence I settled on Age of Homespun and New Historicism and Cultural Materialism’s sentences which use metaphor, simile, idiom and oxymoron (alliteration not included). Let’s try metaphor: “museums are” … “the heart of an urban landscape”… “seeds in the Paris’ urban landscape.” Now a simile: “and like Josephine’s roses they bloom and thrive amidst the brick and concrete.” All together now: “Museums are seeds in the Pariasian urban landscape and, like Josephine’s roses, they bloom amidst the garden of brick and concrete.”

So, how’d I do?

Word Count: 575

Total Edits: 0

Wednesday, August 14, 2013

Ingredient - Add Salt

Salt to cooking is figure of speech to writing.

After reviewing Monday's ingredient, I realized I had more sour sentences than savory, a lot more. So I widened my selection, concentrating on more of those savory sentence samples. Then I sat down and examined the contents, chewing carefully.

These are the salient:

After reviewing Monday's ingredient, I realized I had more sour sentences than savory, a lot more. So I widened my selection, concentrating on more of those savory sentence samples. Then I sat down and examined the contents, chewing carefully.

These are the salient:

- The strange silencethat haunts the interpretation of Sarah Kemble Knight’s Journal (c. 1704) is doubly odd, given the continued prominence of the text in American literature canon. – Narrative and Class in a Culture of Consumption

- Alliteration; Allusion

- Few commodities in Atlantic history can be as humble as the plantation hoe. – The Plantation Hoe

- Personification

- On April 16, 1787 Royall Tyler, Jr. had the pleasure of seeing the first production of his play, The Contrast. – Class Positioning and Shay’s Rebellion

- Cliche

- Even seasoned observers of academic fashionsmay feel giddy noticing the rise of something called the "New Historicism," especially as we had just grown accustomed to pronouncements, whether celebratory or derogatory, that there was no getting" beyond formalism.” – American Literature and the New Historicism

- Metonymy; Paradox; Description

- One thread in the American nineteenth-century discourse of sentiment wraps itself around women's bodies. – Cultural Rhetoric of Women’s Corsets

- Personification & Hyperbole

- If this book were an exhibit, I could arrange it as a room, one of those three-sided rooms you sometimes find in museums, open on one side like a dollhouse, with a little fence or rope across.– Age of Homespun

- Metaphor; Similie

- Any commentator rash enough to pass sentence on a powerful new critical movement before its star has plainly waned is tempting fate. – New Historicism and Cultural Materialism

- Idiom; Oxymoron

- The Victorian novel describes, catalogs, quantifies, and in general showers us with things: post chaises, handkerchiefs, moonstones, wills, riding crops, ship’s instruments of all kinds, dresses of muslin, merino, and silk, coffee, claret, cutlets – cavalcades of objects threaten to crowd the narrative right off the page. – The Ideas in Things

- Metaphor; Idiom

Word Count: 385

Total Edits: 0

Monday, August 12, 2013

Ingredient - Hello! Call me...

Benjamin Franklin was born on Milk Street in Boston...

Read that again. "Benjamin Franklin was born on Milk Street in Boston..." is the opening line about the literary career of Benjamin Franklin and I'm ready to sit at the table and devour the essay. Reason 1: I just finished watching Carolyn Steel's "How Food Shapes Our Cities" which discussed the naming of streets after food and the griddle started popping. Reason 2: Because of Reason 1, I stopped to closely examine the sentence. I noticed it didn't start with the typical introduction of the year of his birth. It begins with a totally random fact that most people probably don't know. They might know he was born in Boston; but would they have known the name of the street?

First impressions matter more in writing than simple introductions of, "Hi, my name is..." unless you're Ishmael. You have to capture the audience interests while providing them with an introduction to the essay topic. Too often I fall into the droll academia introduction which inspires NO interest because the introduction isn't the meat of the writing. And that's wrong. The introduction is the most important part... as my mother always says, "People judge you by your first impression. It's not always right or fair, but they do." Unfortunately, the same applies to writing.

How do you make a great first impression? I have no idea... yet. Let's examine other literary culinary creations. I went to the American Book Review for their article on "100 Best First Lines from Novels" and was proud to know many of them. These are imaginative. However, they don't tell us much about the story (except for: "I am an invisible man.") What they do is make you ask questions, "Who is Ishmael?" and "How did you become invisible?' The reader is engaged like melting butter on pancakes. Otherwise, you'd sit there staring at cold pancakes. Blah!

I have a collection of journal articles concerning literary criticism and started going through them just looking at the first line:

- Two bridges span the Delaware River between Philadelphia and New Jersey, one named for Benjamin Franklin, the other for Walt Whitman. - "The Loafer and the Loaf-Buyer"

- Criticism of Benjamin Franklin's Autobiography, often indistinguishable from commentary on the author himself, oscillates fairly predictably between two positions. - "Urban Bifocals"

- The strange silence that haunts the interpretation of Sarah Kemble Knight's Journal is doubly odd, given the continued prominence of the text in an American literature canon. - "Narrative and Class in a Culture of Consumption"

- The inception of American regionalism is routinely identified by scholars in either Robert Beverly or William Byrd II, both native Virginians who wrote intensely local works which are amongst the enduring literary products of colonial America. - "Industry and Idleness in Colonial Virginia"

- Few commodities in Atlantic history can be as humble as the plantation hoe. - "The Plantation Hoe"

- One thread in the American nineteenth-century discourse of sentiment wraps itself around women's bodies. - "Cultural Rhetorics of Women's Corsets"

Which one appeals the most to you? Why?

Word Count: 514

Total Edits: 0

Friday, August 9, 2013

Ingredient - Grins, Smiles & Laugh-Out-Louds

I love food and I love history, as you may have noticed, so "Jennifer 8. Lee Hunt for General Tso" spoken essay is a great combo meal with the addition of smartly absurd humor. And there's the punchline, humor. I dare you to find an academic paper or academic guide that promotes the use of humor in a paper. If you know of one, send it to me.

Humor combined with skillfully collected knowledge make's Jennifer 8. Lee's spoken essay fun like an all-you-can-eat-buffet. I learned the value of humor, not from cooking, but from my old Biology teacher in high school. Doc entertained a class of Juniors and Seniors with excellently timed stories completely relevant to the subject. This helped me retain the otherwise skeletal information because it was related to a story. Stories beef up and flesh out the facts so they're easier to remember. You may not remember the story verbatim but you remember the gist. I continued to use the Doc's method when I started working for historic sites and museums. I used humorous stories to engage the audience while providing the factual information. This always improved the audiences experience.

However, writing humor into an essay is hard for me because humor requires an audience reaction. How do you write for an audience when you don't know know who the audience is? Even that's not my biggest roadblock, it's really the years of collegiate molding restricted to academic writing that I'm having to break free. Well, there's a book that supposed to help (you knew that was coming right?!): "Writing Humor: Creativity and the Comic Mind." This is supposed to help break down what's funny and what's not, as well as help make flat writing... fluffy? We'll see.

*Okay, so the campus library does not have this book. Actually, it doesn't have any books about writing with humor. Talk about reinforcing the mold! I declare, "I will write with humor. I will make you grin, smile and laugh out loud!"

Word Count: 292

Edits: 1

Humor combined with skillfully collected knowledge make's Jennifer 8. Lee's spoken essay fun like an all-you-can-eat-buffet. I learned the value of humor, not from cooking, but from my old Biology teacher in high school. Doc entertained a class of Juniors and Seniors with excellently timed stories completely relevant to the subject. This helped me retain the otherwise skeletal information because it was related to a story. Stories beef up and flesh out the facts so they're easier to remember. You may not remember the story verbatim but you remember the gist. I continued to use the Doc's method when I started working for historic sites and museums. I used humorous stories to engage the audience while providing the factual information. This always improved the audiences experience.

However, writing humor into an essay is hard for me because humor requires an audience reaction. How do you write for an audience when you don't know know who the audience is? Even that's not my biggest roadblock, it's really the years of collegiate molding restricted to academic writing that I'm having to break free. Well, there's a book that supposed to help (you knew that was coming right?!): "Writing Humor: Creativity and the Comic Mind." This is supposed to help break down what's funny and what's not, as well as help make flat writing... fluffy? We'll see.

*Okay, so the campus library does not have this book. Actually, it doesn't have any books about writing with humor. Talk about reinforcing the mold! I declare, "I will write with humor. I will make you grin, smile and laugh out loud!"

Edits: 1

Wednesday, August 7, 2013

What is this Thing???

What do you do when you have questions built upon questions? You ask more questions! This is frustrating, I know, but it's the only way I know to excavate the foundation of knowledge. Once the foundation is known, only then can I architect the thing.

What is the thing? The truth is, "I don't know... yet." I asked the question, "How are everyday objects that are incorporated in American literature representative of the culture in which the author is writing?" Or "Are they?" Okay, I don't like the word representative because I'm not looking at them as symbols or motifs. The objects in the literature are materials. They are literary artifacts about culture. Or rather 'ideofacts' if I remember my anthropology/archaeology correctly. The book or materials of the literature such as the paper, ink, etc. are the artifacts; however, the ideas within the text are the 'ideofact.' So what do you call an 'ideofact' that is a material object within the text?

Huh....

To help my answer this question, I'm looking at several critical theories and literary criticism: Marxism, New Historicism and Cultural Materialism. Each have valid source for structuring the thing.

Marxism definitely evaluates things in literature but mostly from a commodities standpoint. If I was examining purely the economic structure of things, this would be good. Culture is more than economics, it’s history, religions, and social behaviors such as class, race, and gender. New Historicism includes more of these categories and Cultural Materialism even more so, though with a more contemporary/popular focus. Therefore, I think the New Historicism methodology is best and more complicated. New Historicism requires a tedious structural balance between the education and research of a literary critic AND a historian.

Sighs… Just because I find part of the answer, doesn’t mean it’s going to be easy.

“To Be Continued”

Word Count: 304

Total Edits: 0

Monday, August 5, 2013

Taste Test #1 - Enlightenment

Do other writers use objects to shape meaning into their works? I'm thinking they do, maybe they don't do it consciously but they do it. Since I've amateurishly decoded the formula for how the Wise-ones shaped their essay, I want to apply this new-found knowledge to other texts beginning with period writings from America between the 18th and 19th century. The objects and their meaning in the literature should reflect the culture of their time - this is a theory in cultural studies, which falls under several headings depending on how you view it: Marxism, Cultural Materialism, New Historicism.

Starting with a sampling of literature from 18th century, I'll also be deciphering and sorting through theoretical knowledge of literary criticism. Yay, me! So beware for repetitions and corrections. I don’t expect to get it right my first time out.

The 18th century American literature will be interesting because this was a time of enormous changes in economics, social development, philosophy, the sciences and the aesthetics. These changes transformed the way American writers understood and wrote about the world.

I'll begin with American Literature from 1700 to 1820, otherwise known as the period of Enlightenment, using The Norton Anthology American Literature: Beginnings to 1820, Volume A (8th ed.). First up is 1704-05, when Sarah Kemble Knight keeps The Private Journal of a Journey from Boston to New York.

Taste Test #2: American Renaissance (1820-1865)

Taste Test #3: Realism & Naturalism (1865-1914)

Word Count: 240

Total Edits: 1

Friday, August 2, 2013

Ingredient - Say an Essay!

During my coursework for Creative Non-Fiction several semesters ago, I was assigned the reference text, "The New American Essay." This was it. This was to guide me to my defining medium for my writing format and my style. Well... It didn't. I knew that essays weren't fiction works nor were they considered academic research. But these essays were designed to stretch the limits of the definition 'essay'. The styles represented were more about the creative force rather than the intellectual dissemination of information. But I don't want to write too creatively intellectual.

So, I looked around. I've scattered magazines and toppled books looking for an essay style that "speaks to me." What did this hearing impaired person find, but 'spoken' essays. Have you heard of TED Talks? Some might consider these video essays, but thanks to their translation and transcription program, I read these spoken essays. They are factual information collection and organized as a result of a person's own unique perspective and communicated in an artful and engaging way. That's an essay and exactly what I need.

Typically, these spoken essays are 10 to 20 minutes long... or in written form, 1,500 to 3,000 words. In the case of Carolyn Steel's spoken essay, "How Food Shapes Our Cities," 15 minutes and 40 seconds or 2,857 words. While reading the essay, I was struck by its simplicity, yet the format engaged me every time I read it. Here I've found an essay format to aspire to:

Word Count: 293

Total Edits: 3

So, I looked around. I've scattered magazines and toppled books looking for an essay style that "speaks to me." What did this hearing impaired person find, but 'spoken' essays. Have you heard of TED Talks? Some might consider these video essays, but thanks to their translation and transcription program, I read these spoken essays. They are factual information collection and organized as a result of a person's own unique perspective and communicated in an artful and engaging way. That's an essay and exactly what I need.

Typically, these spoken essays are 10 to 20 minutes long... or in written form, 1,500 to 3,000 words. In the case of Carolyn Steel's spoken essay, "How Food Shapes Our Cities," 15 minutes and 40 seconds or 2,857 words. While reading the essay, I was struck by its simplicity, yet the format engaged me every time I read it. Here I've found an essay format to aspire to:

- Introduce a Question - "a great question, one that is rarely asked"

- Set the Scene - use the landscape of the issue to shape the essay

- The Background - map the history, "how did we get here"

- The Foreground - map the future, "what does it mean"

Word Count: 293

Total Edits: 3

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)